“Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre seeks to unearth and examine the complex, often contradictory, relationship between humans and the yaki, the black crested macaque of Minahasa. Through speculative fiction, I try to navigate the intertwined dynamics of primatology, ecofeminism, and technology. The narratology and immersive experience highlight the intricate bond, the messy relationship between humans and the yaki, reflecting the tangled interactions between species and encouraging audiences to consider their own relationships with the non-human world. Primate Visions: Macaque Macabre is a world both playful and macabre, filled with radical oddities!”

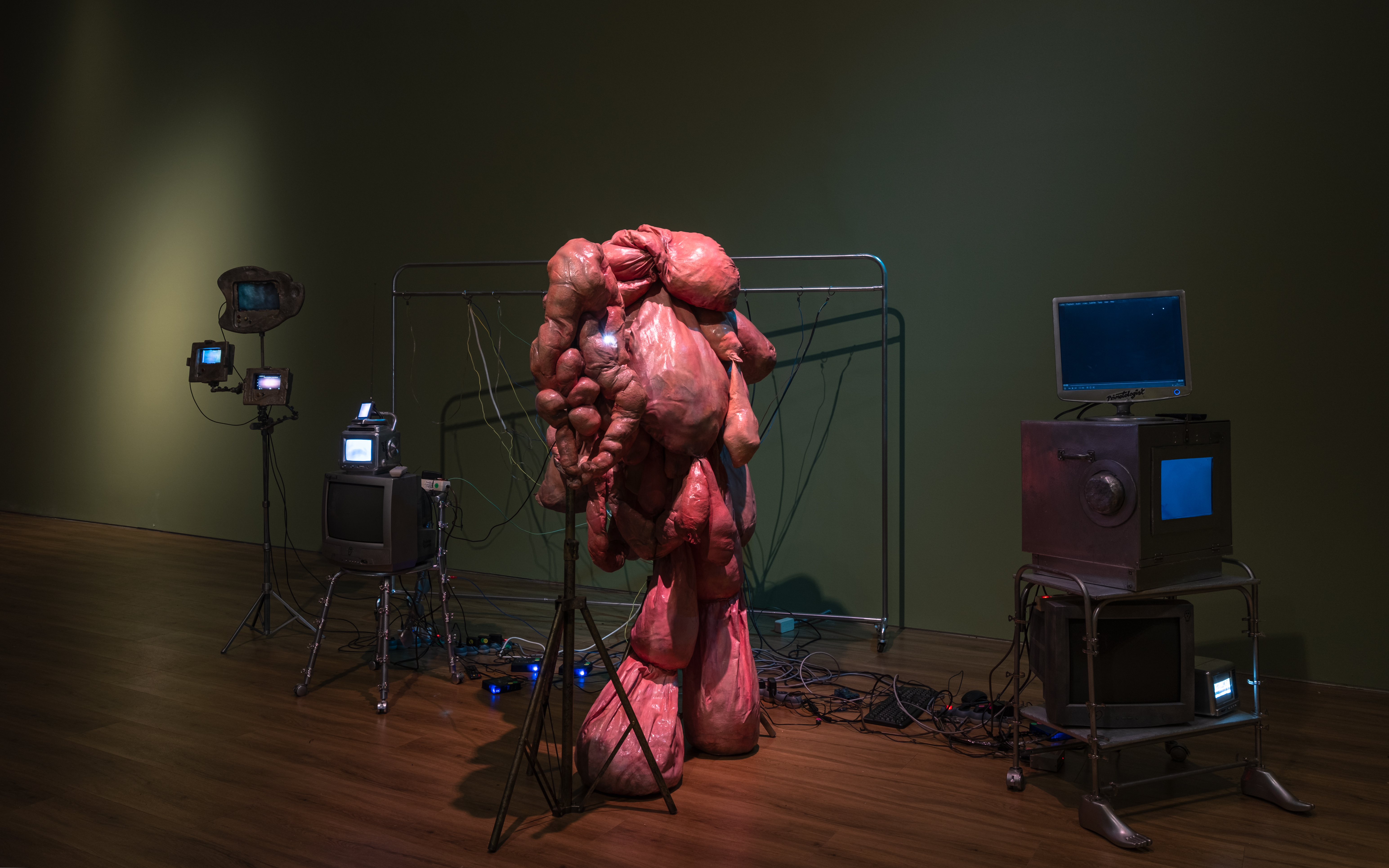

Installation view at Museum MACAN, courtesy of Artist and Audemars Piguet Contemporary

Installation view at Museum MACAN, courtesy of Artist and Audemars Piguet Contemporary

“How do tales of primate lives narrate either nature or culture, or both, but narrate them so as to exclude a reader’s consciousness of mediation, history, and construction?” – Donna Haraway, Primate Visions

Primate Visions; Macaque Macabre is an attempt to expose the multi-layered complexity of connection between human and animal. Through an ethnographic research, amateur primatological research, and speculative fiction, this work investigates an intermingle relation between the endangered species black crested macaque, or in Minahasan it is known as Yaki or Wolay, in which endemic to South Minahasa region, and the indigenous community in the uphill of Po’opo village in which many tales and myths based on the existence of Yaki is told through a ritual called Mawolay (or in English “becoming Wolay” or “becoming the macaque”).

In Po’opo, and Minahasa in general, Yaki is seen from two different perspectives by the indigenous. One as a species that represents the more-than-human relation in which Yaki is understood as part of social structure in everyday life of Minahasan living in the south part of the region. Two, Yaki is conceived as a vermin that sometimes steal villagers’ crops. In recent years, Western NGO, mostly focused on natural preservation and biodiversity, swarmed Po’opo village to educate the villagers on the extinction of Yaki. This created a little tension. For indigenous people, people from NGOs have never experienced strong relationships with Yaki. They came when they knew that the Yaki is hunted and would become extinct, but never understand the structural problems that made indigenous people consider Yaki to be vermin. The land opening in the forest for various reasons, one of them is to open mining sites, renders less food source for Yaki. When Yaki goes downhill, the brutal hunting activities eventually also force them to mass migrate. On the other hand, the land opening in the forest also block some of the food resource of the indigenous, considering many of them still practicing hunting. Yaki become one of the main food resource for the indigenous. This generates a very complex relationship between human and Yaki, which according to the indigenous, people of the NGO lack of the sensibility to understand this conflict.

In the ritual of Mawolay, in which many villagers dressed up as Yaki and walking around in the region, indigenous community tries to mediate this two different assumption to solve the conflict between Yaki and human, that this conflict could be solve without being complicit in violence against nature. Departing from this ritual and the history of relation between Yaki and human in Minahasa, I’m interested in looking and exploring this specific relation between the idea/concept of endangered species and indigenous community. How is it the practice of Mawolay, in which pretty much rooted in ritualistic performance as artistic pracitce, will solve the tension between human and nonhuman in south Minahasa? Considering that Mawolay as a ritual involving a trance-state in which human behaving like a macaque, I’m also interested in looking deeper to this connection of evolution/devolution.

According to Minahasan mythology, the first entities are agender Toar and Lumimuut. However, in Po’opo mythology, one can assumed that Toar and Lumimuut are the embodiment of ancient primates, which potentially share ancestral line with Yaki. In line with this theory of ancestral trajectory, I’m interested in looking the possibility of exploring speculiative fiction in which human and Yaki are come from one ancestor. In Macaque Macabre, this theory will be develop by synthesising Terrence McKenna’s stoned ape theory and Friedrich Engels theory of labour formation as evolution transition from ape to human, which mainly focus on the formation of domestic labour of preparing food while primate become bipedal. My aims to develop this theory is to thinking together with Donna Haraway’s notion that primatology is a story-telling practice, and through this story-telling practice of colliding myth, Mawolay ritual, eco-politics, gendered labour, the entanglement of human-animal, the natural history of Yaki, and the battle of existence, I hope that this work could reflect the future of human nature relation in Minahasa and the world.

Comissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary.

Installation view at Museum MACAN, courtesy of Artist and Audemars Piguet Contemporary

Installation view at Museum MACAN, courtesy of Artist and Audemars Piguet Contemporary

Installation view at Museum MACAN, courtesy of Artist and Audemars Piguet Contemporary

Installation view at Museum MACAN, courtesy of Artist and Audemars Piguet Contemporary